Disclaimer: This content was generated using AI. While I strive for accuracy, I encourage readers to verify important information. I use AI-generated content to increase efficiencies and to provide certain insights, but it may not reflect human expertise or opinions.

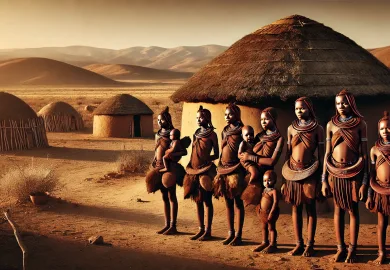

The Tuareg people, often referred to as the “Blue People” due to their distinctive indigo-dyed clothing, are a Berber ethnic group with a rich cultural heritage that stretches across the vast Sahara Desert. They are traditionally nomadic, with a lifestyle that is intricately tied to the harsh environment of the desert. Their culture, language, and traditions have been shaped by centuries of adaptation to this environment, resulting in a unique and resilient society.

The Origins of the Tuareg: A Historical Overview

The Tuareg people trace their origins to the Berber tribes of North Africa. Their history is deeply intertwined with the Sahara Desert, where they have lived for thousands of years. The name “Tuareg” is believed to have originated from the Arabic term “Tawarik,” meaning “abandoned by God,” though the Tuareg refer to themselves as “Kel Tamasheq,” meaning “speakers of Tamasheq,” their native language.

The Tuareg’s history is marked by their role as traders across the Sahara. They controlled caravan routes that connected North Africa with sub-Saharan Africa, facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures. This trade network made the Tuareg an integral part of the region’s economy and cultural exchange for centuries. Their knowledge of the desert’s intricacies allowed them to navigate the harsh terrain and thrive where others could not.

In addition to their role as traders, the Tuareg were also known as fierce warriors. They defended their territories and way of life from various invaders, including colonial powers during the 19th and 20th centuries. Despite these challenges, the Tuareg have maintained their cultural identity and continue to live according to their traditions.

Tuareg Society and Social Structure

Tuareg society is traditionally organized into a hierarchical system based on clans. Each clan, or “tawshet,” is made up of several extended families and is led by a chief, known as an “amenokal.” The amenokal is responsible for making decisions on behalf of the clan, particularly in matters of justice, warfare, and relations with other clans. The position of amenokal is usually hereditary, passing from father to son, though it can be influenced by the consensus of the clan members.

The Tuareg social structure is also characterized by a caste system, which includes nobles, vassals, artisans, and slaves. The nobles, known as “imajeghen,” are the ruling class and are responsible for leading the clan in times of war and peace. The vassals, or “imghad,” are free Tuareg who serve the nobles but have their own social standing. Artisans, called “inaden,” play a crucial role in Tuareg society by crafting tools, weapons, and jewelry, often incorporating intricate designs that hold cultural significance. Lastly, the slave caste, known as “iklan,” historically consisted of individuals captured in raids or inherited through generations, though slavery has been largely abolished in modern times.

Women in Tuareg society hold a relatively high status compared to other nomadic groups in the region. They have significant influence within the family and are responsible for managing the household, raising children, and maintaining the family’s wealth, often in the form of livestock. Tuareg women are also the keepers of cultural traditions, such as music, storytelling, and the oral transmission of history.

Tuareg Language and Art: Expressions of Identity

The Tuareg speak Tamasheq, a Berber language written in the ancient Tifinagh script. This script, composed of geometric symbols, is one of the oldest writing systems still in use today. Tamasheq is not only a means of communication but also a vital aspect of Tuareg identity. The language has been passed down through generations, and its preservation is a source of pride for the Tuareg people.

Art is another important expression of Tuareg identity. Tuareg artisans are renowned for their silverwork, particularly the creation of intricate jewelry. One of the most famous pieces is the “Cross of Agadez,” a symbol that comes in various forms and is often passed down as an heirloom. These crosses are not just decorative; they hold deep cultural significance and are believed to offer protection to the wearer.

Leatherwork is another traditional Tuareg craft. Tuareg artisans create beautifully decorated saddles, bags, and cushions, often using leather dyed in vibrant colors. These items are both practical and symbolic, reflecting the Tuareg’s deep connection to their nomadic lifestyle and the desert environment.

Tuareg music and poetry are also central to their cultural expression. Tuareg songs often tell stories of love, war, and the beauty of the desert. The “tinde,” a drum made from a mortar covered with goatskin, is a common instrument in Tuareg music, providing a rhythmic foundation for songs and dances. Poetry, known as “assouf,” is a way for the Tuareg to express their emotions and experiences, often reflecting on themes of solitude, longing, and the harshness of the desert.

The Tuareg Today: Challenges and Adaptations

In recent decades, the Tuareg people have faced numerous challenges as a result of political, environmental, and social changes in the Sahara region. The establishment of national borders by colonial powers in the 19th and 20th centuries disrupted the traditional nomadic routes of the Tuareg, forcing many to settle in towns and cities. This transition from a nomadic to a sedentary lifestyle has had profound effects on Tuareg society, including the loss of traditional knowledge and practices.

Climate change has also had a significant impact on the Tuareg. The Sahara Desert has become increasingly inhospitable due to prolonged droughts and desertification. These environmental changes have made it difficult for the Tuareg to sustain their traditional way of life, particularly their reliance on livestock herding. Many Tuareg have been forced to migrate to urban areas in search of work, leading to the erosion of their cultural identity.

Despite these challenges, the Tuareg continue to find ways to adapt and preserve their culture. In some regions, they have formed cooperatives to promote their traditional crafts, such as jewelry and leatherwork, to international markets. This has provided a source of income and helped to sustain their cultural heritage. Additionally, there has been a revival of interest in Tuareg music, with Tuareg bands gaining recognition on the global stage for their unique blend of traditional and modern sounds.

The Tuareg have also been involved in various political movements, seeking greater autonomy and recognition of their rights. In some countries, such as Mali and Niger, Tuareg groups have engaged in armed struggles for independence or greater political representation. These conflicts have often been rooted in grievances over marginalization, economic exclusion, and the loss of traditional lands. While some progress has been made in addressing these issues, the Tuareg continue to face significant challenges in achieving their goals.

In conclusion, the Tuareg people are a resilient and culturally rich group with a history that is deeply intertwined with the Sahara Desert. Their society, language, and art reflect their unique way of life and their ability to adapt to the harsh environment of the desert. Despite the challenges they face in the modern world, the Tuareg continue to preserve their cultural heritage and maintain their identity. As they navigate the complexities of the 21st century, the Tuareg remain a testament to the enduring strength of human culture and the power of tradition in the face of change.