Disclaimer: This content was generated using AI. While I strive for accuracy, I encourage readers to verify important information. I use AI-generated content to increase efficiencies and to provide certain insights, but it may not reflect human expertise or opinions.

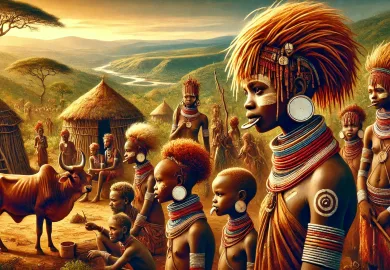

The Maasai people, a semi-nomadic ethnic group, inhabit regions of southern Kenya and northern Tanzania. Known for their distinct attire, deep-rooted customs, and unique way of life, the Maasai have preserved their culture despite modern influences. This article delves into the essential aspects of Maasai culture, exploring their social structure, rites of passage, diet, and traditional beliefs. As we uncover these aspects, it becomes clear that the Maasai culture is not just a way of life but a rich tapestry of history, tradition, and resilience.

Social Structure and Community Life in the Maasai Culture

The Maasai community is built around a tightly-knit social structure that emphasizes unity and collective responsibility. The society is organized into age groups and clans, with each playing a vital role in maintaining order and harmony. Elders hold significant authority, making key decisions regarding the community’s welfare and conflict resolution. These elder councils are instrumental in preserving traditions and passing down wisdom from one generation to the next. Additionally, communal living is central to the Maasai, as families share resources and support one another in daily tasks such as herding cattle, building homes, and safeguarding the community.

The Maasai live in enkangs, or traditional homesteads, made up of several mud huts encircled by thorny enclosures to protect livestock from predators. Each enkang is a testament to the cooperative spirit of the Maasai people, with every member contributing to the construction and maintenance of these homes. This communal living reinforces the values of solidarity and mutual respect, ensuring that the needs of every individual, from the youngest to the eldest, are met.

A unique feature of Maasai society is the age-set system, where individuals progress through various life stages as a group, from childhood to warriorhood and eventually elderhood. Each stage is marked by specific roles and responsibilities, with young men, or morans, tasked with protecting the community and demonstrating bravery, while women take on nurturing roles within the family. The age-set system not only organizes Maasai society but also fosters a strong sense of identity and belonging, as individuals grow and mature together within their group.

Rites of Passage and Ceremonial Practices

Rites of passage are integral to Maasai culture, marking the transition from one stage of life to another. The most significant ceremonies revolve around the transition from childhood to adulthood. For young boys, the journey begins with circumcision, which is seen as a rite of initiation into manhood. This ceremony, known as Emuratare, is a test of endurance and bravery, as boys are expected to endure the process without showing signs of pain. Successful completion of this rite earns them the status of moran, or warrior, a highly esteemed role within the Maasai community.

For young girls, circumcision, although controversial and increasingly discouraged, has traditionally been a rite of passage into womanhood. The practice is closely linked to the community’s concepts of purity and readiness for marriage. However, with growing awareness and external influence, many Maasai communities are beginning to replace this rite with alternative ceremonies that honor cultural values while promoting the health and rights of girls.

In addition to rites of passage, the Maasai hold elaborate ceremonies to celebrate marriages, births, and harvests. These ceremonies are marked by singing, dancing, and the wearing of vibrant shukas (traditional red cloth) and elaborate beadwork, which symbolize identity and status. The unity of the community is expressed through these collective celebrations, where Maasai oral traditions are shared, and their rich history is passed on through songs and storytelling.

The Maasai Diet and Traditional Livelihood

Cattle hold immense cultural and economic significance in Maasai society. The Maasai are predominantly pastoralists, with their livelihood revolving around the herding of cattle, goats, and sheep. For the Maasai, cattle are more than just a source of food; they represent wealth, social status, and spiritual connection. The traditional Maasai diet is primarily composed of meat, milk, and blood, with cattle blood being consumed on special occasions or as a source of strength during illness or after childbirth.

Milk, often mixed with blood, forms a staple part of the Maasai diet and is consumed daily. The Maasai’s intimate relationship with their livestock is evident in their deep knowledge of animal husbandry, passed down through generations. This knowledge includes techniques for grazing management, seasonal migrations, and maintaining the health of their herds in challenging environments. Despite the influence of modern agriculture and dietary practices, many Maasai communities continue to adhere to their traditional diet, viewing it as essential to their identity and way of life.

While cattle rearing remains central, the Maasai have adapted to changes in their environment and economy by diversifying their sources of income. Many Maasai communities now engage in small-scale farming, trade, and tourism-related activities. Beadwork, in particular, has become a significant source of income for Maasai women, who craft intricate jewelry that is sold in markets and to tourists. Despite these adaptations, the Maasai’s deep connection to their cattle and land remains unwavering, reflecting their resilience in maintaining their cultural heritage amid modernization.

Spiritual Beliefs and Relationship with Nature

The Maasai’s spiritual beliefs are deeply intertwined with their environment and daily life. They practice monotheism, worshipping a deity known as Enkai or Engai. Enkai is believed to be a dual-natured god, embodying both benevolent and wrathful aspects. The benevolent Enkai Narok (Black God) is associated with blessings, rain, and prosperity, while Enkai Nanyokie (Red God) is linked to drought and hardship. This duality reflects the Maasai’s dependence on nature, particularly rainfall, for their survival, as they rely on natural cycles to sustain their cattle and crops.

Rituals and prayers are central to Maasai spiritual life, often conducted by elders and spiritual leaders known as laibons. The laibons play a crucial role in guiding the community, performing rituals to invoke blessings, predict the future, and protect the community from harm. The Maasai’s spiritual connection to their environment is evident in their respect for natural resources and their sustainable practices in herding and land management.

The Maasai worldview emphasizes harmony with nature and the community. This philosophy is reflected in their traditional practices, such as rotational grazing, which prevents overuse of land and ensures the regeneration of pastures. The Maasai’s respect for their environment is also seen in their reluctance to exploit natural resources beyond what is necessary for survival, ensuring that the land remains fertile for future generations. As custodians of their land, the Maasai embody a sustainable lifestyle that balances human needs with ecological preservation.